With justified outrage, V.S. Naipaul once wrote that a Peronist had warned him there are two kinds of torture: bad torture and good torture. Bad torture is what the enemies of the people do to you; good torture is what you inflict on the enemies of the people.

Venezuela embodies the chilling persistence of this aberration. UN reports, along with the abundant personal and journalistic testimony documenting how the Chavista regime destroys its opponents, have failed to erase in some quarters the certainty that anyone who does not think like them deserves to be tortured.

Something similar is happening with anti-imperialist thinking—a shiny badge marked by the dichotomy of bad imperialisms and good imperialisms. We raise the issue because it is surprising to see Laura Restrepo’s sudden solidarity with Venezuelan sovereignty, underscored by her decision to withdraw from the Hay Festival as a gesture against “Yankee imperialism.”

The problem is that there is no way to verify that she has spent these years also questioning the aggressive presence of the governments of Russia, China, Iran, Cuba, and Colombian guerrilla groups in Venezuelan affairs.

In the Cuban case, one can understand it as a gesture of gratitude toward her habitual hosts at events controlled by the Castro dictatorship. But she might at least have said something about the actions of the other countries that are suffocating Venezuela through imperial practices, including Iran and its fearsome, women-killing theocracy.

This timely and resounding silence makes it possible to conclude that Venezuela has so far benefited from “good imperialisms,” and that Restrepo has decided to save Venezuelans only from the “bad imperialisms” that might arrive in the future.

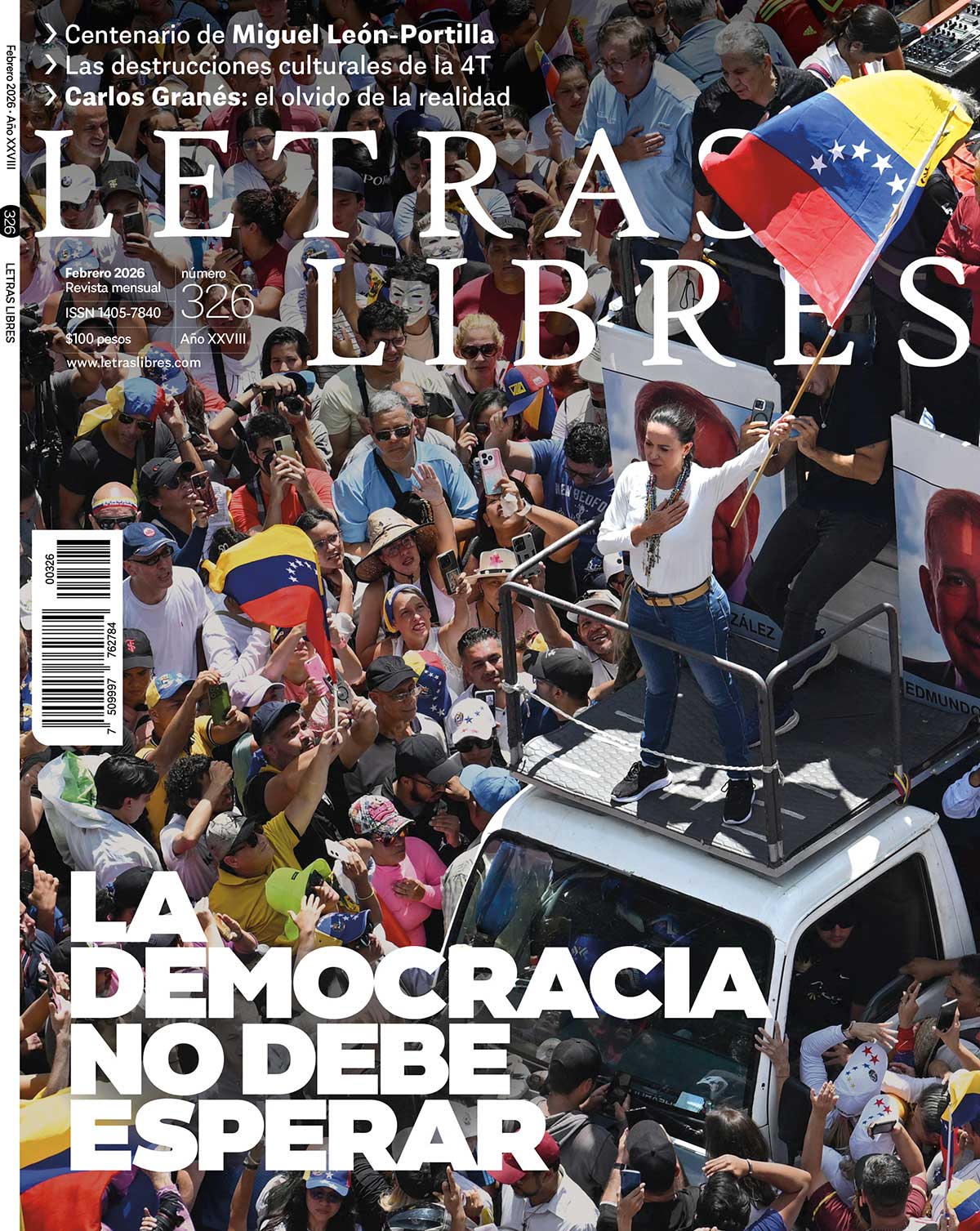

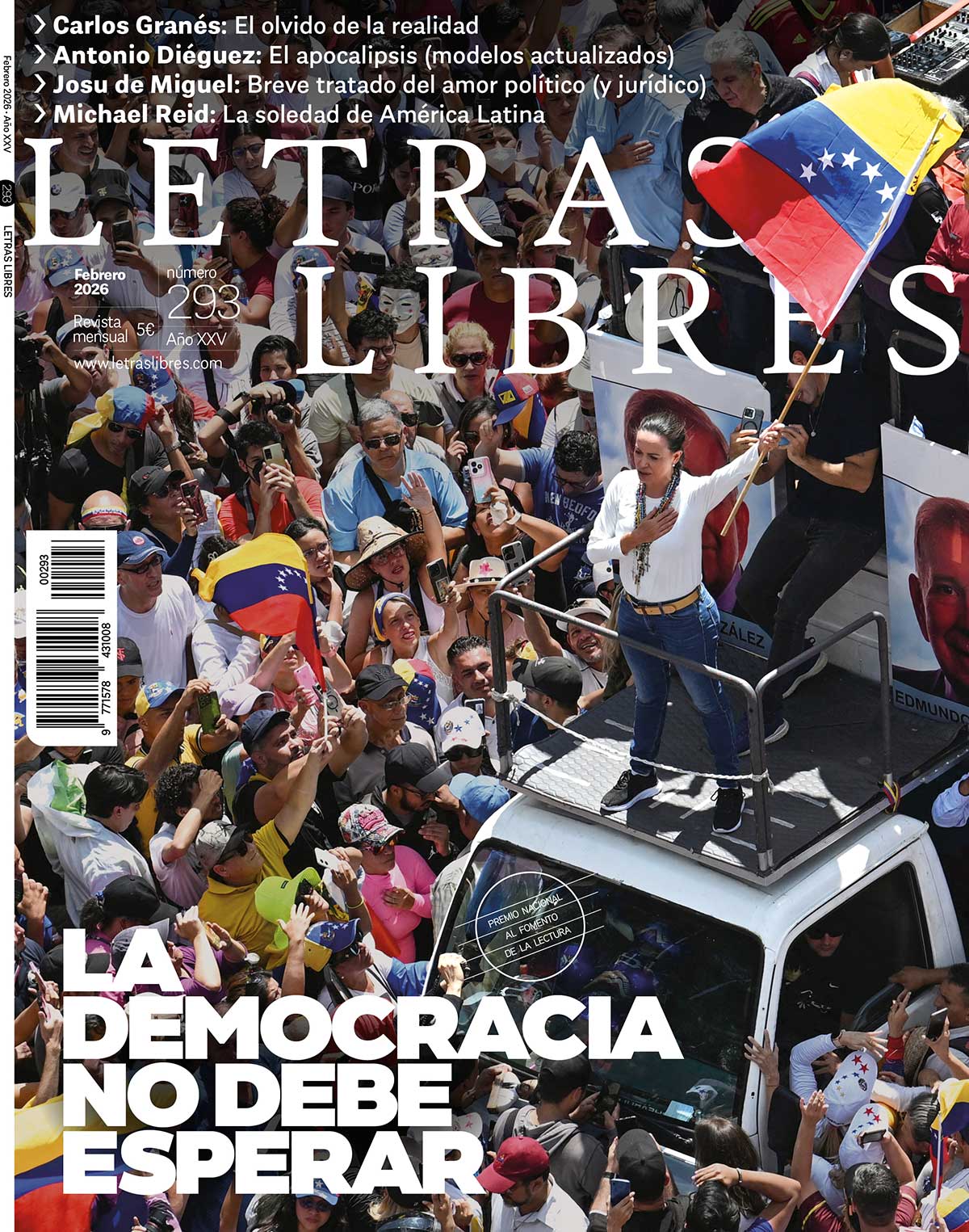

As we noted, her most recent militant act is encapsulated in the letter explaining to the Hay Festival organizers that she will not attend the event because they dared to invite the Venezuelan leader María Corina Machado, whom she describes as an “active supporter of U.S. military intervention in the Americas.” She offers not a single direct quotation to back up this claim, nor does she apply the rigor one would expect from someone who is, in essence, a respected journalist; instead, she merely repeats slogans produced by the propaganda laboratories of the Venezuelan dictatorship.

Is this how journalism has always been practiced? Are her works of fiction a controlled emanation of those totalitarian powers she does not even offend with an adjective?

In the realm of personal sympathies and antipathies, no one can intervene. Chavista groups broke María Corina Machado’s nose with their fists, barred her from running for office, and forced her into hiding. They likewise persecuted, arrested, and murdered her collaborators—but one might suppose that Restrepo’s anti-imperialist silence in those instances stemmed from personal animosity.

More difficult to explain is Restrepo’s muteness when she failed to denounce the crude electoral fraud committed by Chavismo in 2024, failed to question the imprisonment of thousands of people during those days, and failed to express a single word of solidarity with the 119 women currently arrested, tortured, and abused in Venezuelan prisons. Even her anti-imperialist silence was not broken in 2015, when the Chavista Guard marked the homes of Colombian families to demolish them with tractors and expel their inhabitants from the country.

Yes, now we are talking about anti-imperialism. As attested by the personal testimony of many Venezuelans who, out of fear, ask that their names never be mentioned, as well as by reports published by BBC News mundo, The Washington Post, Infobae, and by texts from María Werlau and Adriana Boersner-Herrera, among others, the barbarism Venezuela has endured for decades is also the result of the aforementioned interference by Cuba, Russia, Iran, and far-left Colombian guerrilla groups—factors without which such a disastrous dictatorship could not survive, given the profound rejection it inspires among Venezuelans. It would have been splendid to hear Restrepo say at that moment: “Imperialist intervention is not debated; it is rejected outright.”

In short, what does Restrepo seem to be telling the world and the Hay Festival? I will not participate in events where militant uniformity is not guaranteed, where my voice and that of my allies are not the only ones allowed to be heard.

It is hard to imagine that a prestigious and plural gathering like the one held in Cartagena could accommodate such a capricious demand from any of its guests. But for Restrepo’s consolation, there will always be the FILVEN book fair organized in Caracas—an event where no bothersome or discordant noise will disturb her anti-imperialist ears. There she will be welcomed with military honors; there she will be assured that only applause, praise, and opinions identical to her own will be heard, because divergent voices will have been completely crushed—some terrorized in their homes, others in prison, others in exile, and a few in the cemetery.

I imagine that Laura Restrepo’s very recent relationship with democracy remains complicated. Perhaps that is why she feels no shame in refusing to share the air with a persecuted political leader who does not share her views—nor does her anti-imperialist fury pause to consider that María Corina Machado won an election in which 67 percent of Venezuelans voted for her and for Edmundo González Urrutia.

That is the tragedy of anti-imperialist enlightenment. Restrepo knows what truly suits Venezuelans; she knows we were mistaken to want oxygen tanks in our hospitals instead of glimpsing, in our ports, dozens of ships carrying free oil to Castroism.

There is no need to go on. Laura Restrepo knows what the only desirable future is for millions of Venezuelans: from here to eternity, to endure corruption, refugee caravans, humiliating poverty, plunder, and death—so that she can calmly attend literary events around the world.

And sing the praises of anti-imperialism, of course.