With national elections just days away, the daily worries of Bolivians can be summed up in three questions: How can they stretch incomes that no longer cover the basics? How can they find gasoline or diesel to get anywhere? And—though none of the contenders inspires much faith—which one might offer a real way out of economic collapse and uncertainty?

An equally urgent concern is the disappearance of U.S. dollars. Importers can’t pay for supplies abroad or settle even minimal debts with foreign partners. Ordinary citizens can hardly plan trips overseas or pay for now-essential services such as Netflix. The reason is simple: the Central Bank’s foreign reserves have all but dried up. In 2014, they stood at $13.46 billion; by 2022, they had plunged 94.7% to $709 million. The official exchange rate is still 6.96 bolivianos to the dollar, but speculation rules the streets. Since early 2023, the parallel dollar has climbed steadily, now trading between 15 and 18 bolivianos and showing no sign of stopping. The effect on purchasing power has been brutal: everything costs more, imported goods have vanished, and inflation—the tax that spares no one—is rampant.

Between January and June 2025, official inflation reached 15.5%, more than double the government’s annual target. Year-on-year inflation is above 24%. Food prices are up 38%, and personal hygiene and cleaning products have risen by 41%. Bolivia now faces its highest inflation in four decades, making it Latin America’s second-most inflationary economy.

How did it come to this? And who has been at the helm over the past 20 years?

When Evo Morales took office in 2006, GDP was $9.55 billion, and poverty affected nearly 60% of Bolivians. Thirteen years later, GDP had risen to $40.29 billion, and poverty had fallen to 34.6%. Morales, who served as president until 2019, claimed the boom as his achievement. Yet economist Rómulo Chumacero found that growth owed far more to a once-in-a-generation commodity bonanza than to government policy. In fact, domestic policies likely dragged growth down by 2% to 6.1% of GDP per capita. Morales was fortunate: he inherited investments made by previous governments and enjoyed record-high international prices for Bolivian exports. There was no miracle—just a windfall.

Now, as citizens queue for hours to buy a liter of gasoline or cooking oil, the questions linger: Why didn’t Morales use that historic opportunity to build a productive economy? Why did he cling to short-term spending and redistribution, binding the country to gas and mineral dependency?

Morales is not the only one responsible. His former economy minister—and president since 2020—Luis Arce Catacora, often hailed as the “architect” of the so-called miracle, doubled down on the Productive Social Community Economic Model, a statist framework designed to “lay the groundwork for a transition to the new socialist mode of production.” He inherited a fragile economy but refused the reforms needed to stabilize it. Dollar shortages, eroding confidence, and macroeconomic fragility have deepened, compounded by a split within the ruling Movement for Socialism (MAS) that has weakened governability.

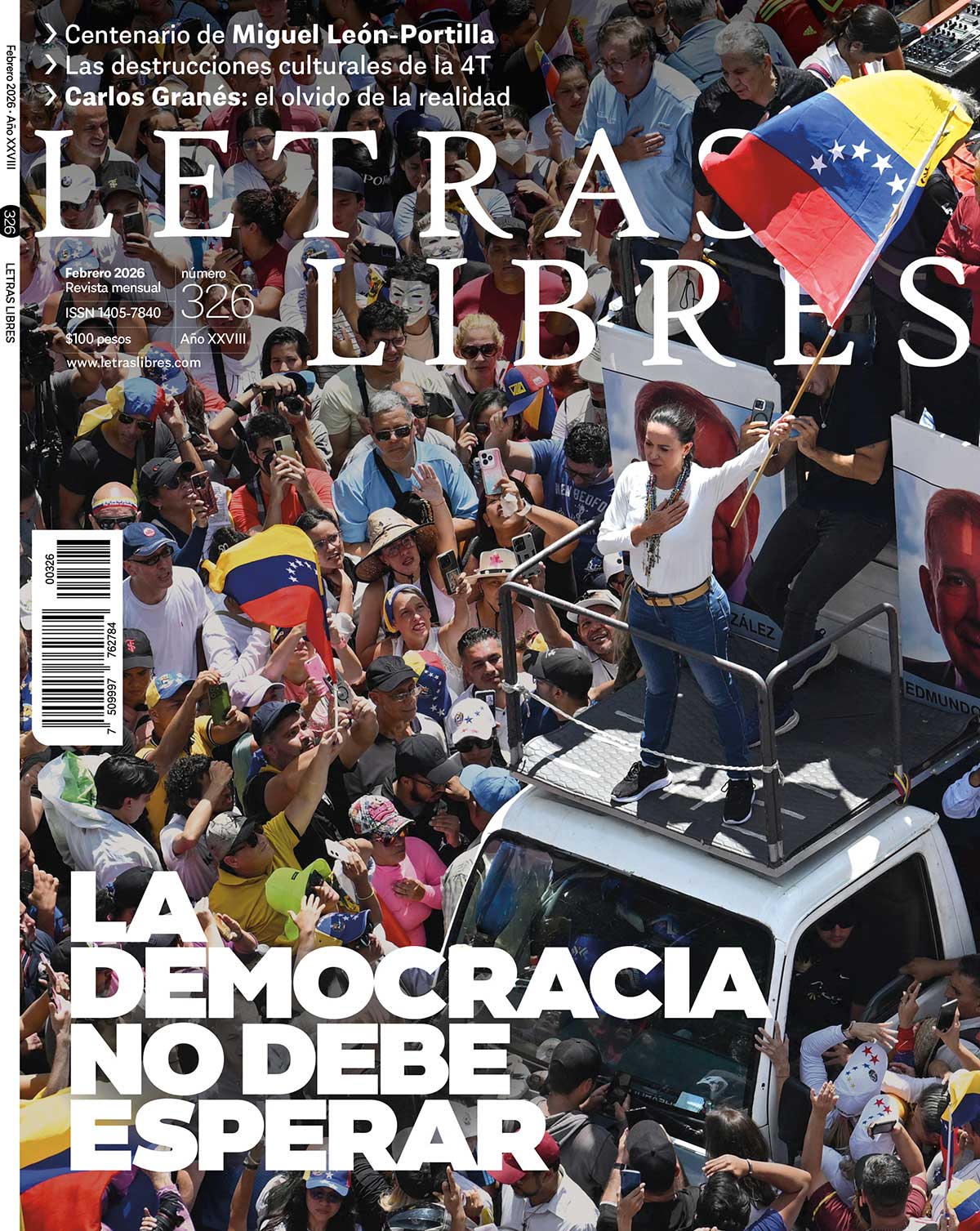

The elections now unfold against this backdrop. Public frustration is at a record high: 85% of Bolivians say they distrust the national government. Center-right candidates lead the polls, capitalizing on the ruling party’s failures, the economic freefall, and MAS’s fragmentation.

Yet uncertainty overshadows everything. For most Bolivians, the question is no longer who wins, but whether the next government can summon the political will to halt the slide before it explodes into political and social chaos. Meanwhile, Morales—permanently barred from office and sidelined within his own party—still issues threats: “If the right wins, let’s see if they can endure.”

Originally published in Conversaciones globales, a project of Letras Libres funded by the Open Society Foundations.