Ivan Krastev, born in Bulgaria in 1965, director of the Centre for Liberal Strategies in Sofia, Bulgaria, and chairman of the Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) in Vienna, is one of today’s leading thinkers on liberty, democracy, and political discontent. He is the author of illuminating books like After Europe, The Light That Failed (with Stephen Holmes), and Is It Tomorrow Yet?. He is also a contributing editor at the Financial Times and writes regularly for other international outlets. A philosopher by training, Krastev has an uncannily perceptive way of analysing contemporary events, spotting unexpected trends and patterns, and a knack for expressing them through memorable turns of phrase and striking, often amusing anecdotes.

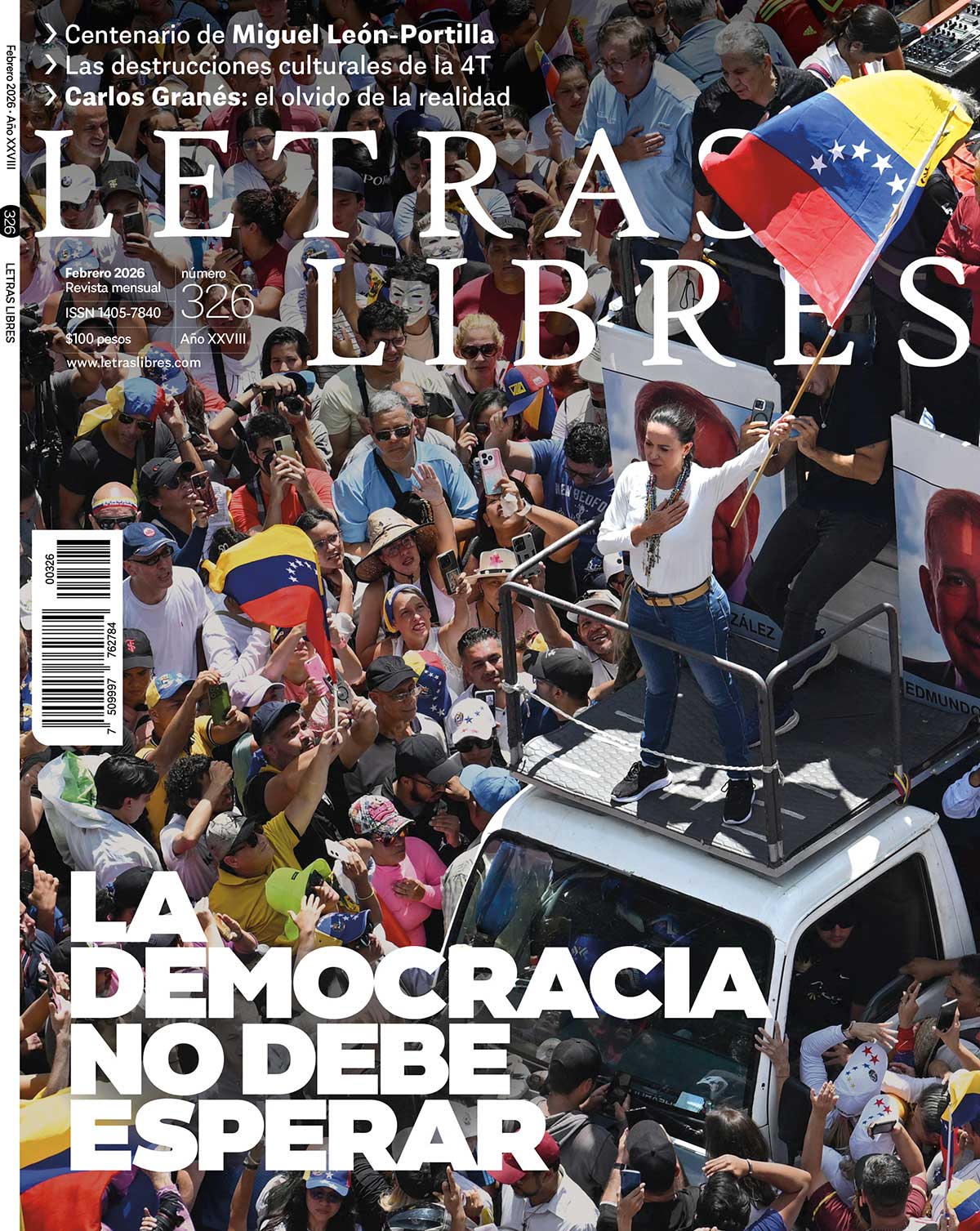

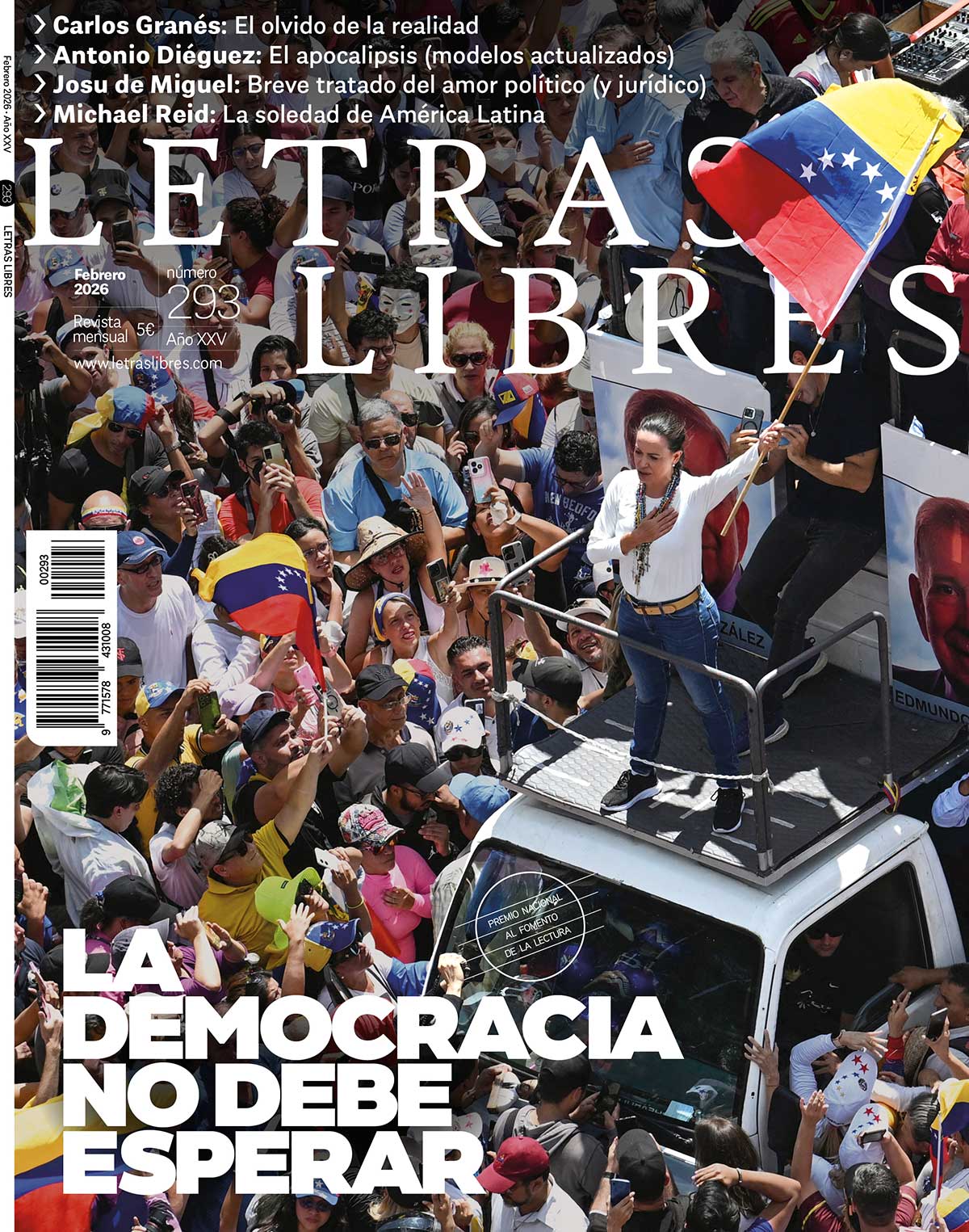

Krastev was in Mexico for La Libertad de Vuelta, a conference organized by Letras Libres and supported by Open Society Foundations and Arte y Cultura, commemorating the 35th anniversary of the Encuentro Vuelta, which, just after the fall of the Berlin Wall, brought together many Eastern European intellectuals and dissidents alongside many writers from Western Europe and the Americas. In this conversation, held at El Colegio Nacional, we talked about how we see the 1990s now compared with how we lived them then, the challenges Europe faces, the effects of Trump’s presidency, and why we are living in revolutionary times.

We often remember the 90s as a period of optimism, but you say it wasn’t exactly like that.

We see all this period as the same period. It was not like this. The end of the Cold War was perceived as a crisis in the West. Because if you go even to the famous The End of History? piece by Fukuyama, and we’re talking about the article, which had a question mark, what is very important in this text published in the spring of 1989 is that there was not any expectation that the Soviet Union was going to disintegrate. The idea was simply that it stopped being a communist state and that they were going to be much more cooperative in their relations.

Later, with all this talk about the New World Order of George H. W. Bush: when he said we are after a war, he didn’t mean the Cold War. It was the Kuwait War. And the Kuwait War was perceived as the model of the world to come, which means the Soviets and the Americans acting together. Obviously, the Soviets are the minor shareholder, but at the same time, for several years, there was not a single veto in the UN Security Council. And then came the disintegration and the war in Yugoslavia, which was perceived extremely dramatically because the idea was, what if this was going to happen in the Soviet Union? And then there was this major focus of the Americans on the Soviet nuclear missiles and then the negotiations with Ukraine, the negotiations with Kazakhstan.

Secondly, when you listen to the interpretations, even of Americans in the 21st century, they are going to take the credit for the disintegration of the Soviet Union. But back then, this was not the American official policy. President Bush went to Kiev and said, do not vote for independence. And I’m saying this because, incidentally, first, these were the early years. And these early years were so much about uncertainty that one important decision was taken, and this decision now could be questioned. And the decision was, we’re not going to create any new institutions. We’re simply going to integrate what came from the East into the institutions of the West.

The major story is, do you believe that you can change the East without changing the West? For many people, it was unclear to what extent the Western liberal democratic model was dependent on the Cold War, on the existence of the Soviet Union as a particular type of enemy. And then the German model became the model for integration.

East Germany was basically integrated in West Germany. Eastern Europe is going to be integrated in the European Union. And this is not by accident that in a strange way now, in the 1990s, people were envying East Germans. They said, oh, it’s so good, they get all this money, it’s much easier for them. They have the language, they have the opportunities.

That has changed a bit.

Now East Germans are the most bitter, frustrated and resentful of all East European countries that came to the transition.

So the question is that it came as such a surprise that nobody was ready to experiment. And as a result of it, these kinds of fears are forgotten. There was a moment of euphoria, and this moment was after the NATO operation in Kosovo.

This euphoria was based on different things, because in a strange way, it’s a tragic war, because it was not a war about oil. It was not about geopolitical importance -who cares about Kosovo? It was a kind of a classical humanitarian war.

But the problem with it is that it cannot be replicated anywhere. You can do it in Kosovo and nowhere else. And it was a war in which basically NATO didn’t lose a soldier, or justa few.

And then this has, by the way, a very negative effect on Russia. During the bombing of Yugoslavia, 38% of the Russians changed their view of the West from positive to negative. And this explains one of the interesting phenomena of today. In the context of Russia’s war in Ukraine, there is a lot of talk about war. And you’re going to hear a lot of European politicians saying this is the first big war in Europe after World War II. The Yugoslav war has disappeared.

But it has disappeared because we don’t know how to talk about it. So secondly, and this is another important topic for me, is that now when you look back to 1989, we see very important things that we had not seen then and we see now. For us 1989 was simply the liberal revolution.

But it depends where you stay.

Right. If you’ve been in Afghanistan in 1989, this was the high hour of radical Islam. The Taliban had defeated a superpower like the Soviet Union. If you have been in China, suddenly it turns out that the resilience of the communist system is much stronger than we expected. If, for example, you have been in South Africa, and this is what Elon Musk saw, it was the real end of the white colonial power. So suddenly all these other ghosts of 1989 are coming back.

And for the American government now, the most important minority is the white South Africans. Suddenly now people understand that probably Tiananmen was more important than the fall of the Berlin Wall, and as a result of it we start to question certain assumptions which do not hold anymore. For me the lesson is different.

When now everybody is talking about Trump, what’s happening, this is extremely important. Trump’s changing sides politically is as important as Gorbachev’s changing sides. So from this point of view it’s one thing to have a crisis of liberal democracy where the United States continues to support liberal democracy.

And it’s totally different if the United States is changing sides and people pretend that it’s not true. It’s not. It does not mean that liberal democracies are going to disappear, by the way, the communist regimes of North Korea and Cuba have survived all these years.

But of course this is a totally different geopolitical situation. And I’m saying this because while now everybody is focused on Trump and the crisis of liberalism, probably there are many other things that are happening in other places that we don’t see. And this is important in terms of what we are learning from 1989.

There was one thing about 1989 and about optimism which is different from now, not only for liberals but for everybody. Part of the magic of 1989 was that for a short period of time almost everybody had the feeling that they were winning.

For many people on the left, Gorbachev was so important. This was the crisis of communist regimes, but it was kind of a triumphal socialist idea, so we are going to liberate socialism from the communist past.

For people on the right, basically, the major enemy was defeated. For the liberals there was a revolution, but it was a peaceful revolution. So for a very short period of time, 1989 was the moment in which everybody had the illusion that the future was on their side.

So now even those who are winning, I mean the illiberal forces in some countries, I don’t see optimism there. In a certain way you have these kinds of apocalyptic anxieties. And this is very different.

It’s not that liberals are unhappy. The problem is that illiberals do not have the feeling that history is changing and it’s on their side from now on.

You think we are in revolutionary times. You recently published “Liberalism in the End Times”, in Prospect.

I always believed that liberalism never had a good time during a revolutionary change.

We have normally two types of liberalism that we know historically. One is a pre-revolutionary liberalism, which quite often comes from the most progressive part of the governing elites. And it tries to give much more rights to the people and to include much more people in society. And to be honest, it tries to prevent revolution.

And then you have the post-revolutionary liberalism, people like Benjamin Constant and others, who had been earlier supporters of the revolution and then basically had been very much traumatized by its excesses. So they’re trying to guarantee that the terror is not going to come back.

In your article, you mention an anecdote told by Michael Ignatieff. Someone asks Abbé Sieyès what he’d done during the Revolutionary Terror. “I survived”, he says.

This is an important story because in the time of a revolutionary change, it’s not about rules, it’s not about checks and balances, it’s about grabbing the political imagination of the people. And it can go, by the way, in different directions.

And as a result of it, any type of moderation, any type of constraint, is not perceived well. In this time, politics is really like this, the game in which you should do something that is transgressive. And this makes you popular, it makes you legitimate, because people are ready for change, for any change. It cannot go forever.

Every revolution, first of all, is in the plural. Every revolutionary government in a certain way is not simply a coalition of different parties, but of different revolutions.

We can see that in the United States nowadays.

In my view, the most important part of this revolutionary moment is that every identity is going to be changed. For example, for sure, Trump changed the Republican Party.

He’s changing also the identity of the United States. He basically said to the Americans, Our exceptionalism was our vulnerability. He said, We don’t want to be better than others.

We simply want to be stronger than others. But when America is changing, everybody else is changing. China is changing, Europe is changing, as we see in a dramatic way.

So as a result of it, in five or ten years, the game is different, the players are different.

Do you think, as many people are saying, that this is going to be the end of liberalism?

No. But it’s not going to be the same type of liberalism. It’s going to be based on certain experiences that are going to happen in these five or ten years. In certain respects, things for sure are going to be the same, like limited power and so on. But what it means to be a limited power in the AI age, it’s not the same as it was before.

And this combination between technological revolution and political change, obviously, all these climate changes which are going to happen, regardless of what you do or don’t, are creating a totally new situation. And in my view, the stupid question is to try to see how to keep the status quo, defending the status quo. It’s a self-defeating game.

The problem is how you try to imagine a future in which certain things that are important for you, you try to shape them. It’s going to be different from place to place. There are going to be global trends, but there are going to be a lot of choices.

It’s not going to be based on big theories. For example, I hope I’m wrong, but my feeling is the 20th century has died politically. The 20th century created these two major experiences, fascism and communism, that were very much structuring the life of society.

Both worlds are dead. You cannot mobilize with them. So, Biden was talking about fascism on the right. He didn’t win. And the right was talking about communism or Mamdani in New York. And they didn’t win.

We’re going to be in charge of the new worlds. And traditionally, societies are governed by the poverty of the imagination. Because for the people, it’s very difficult to imagine something different than what they see or what they know.

But there are moments in which society is governed by the power of the imagination. And it could be also a crazy imagination. And they don’t need to be consistent at all.

In a moment like this, intensity overthrows consistency. And I do believe that in a moment like this, it is going to play differently in different places. Because also, paradoxically, in this moment, history comes back.

And this history is quite national. And also, it’s not easy to understand the other side. Because the other side is not what it used to be.

And what do you think is going to happen with Europe?

For Europe, the challenge is the biggest of all. Because Europe was the biggest winner in the previous three decades.

In the beginning of the 20th century, Europe was the world. In one way or the other, European empires had been running most of the world. So, it’s not by accident that World War I is also called the European War.

And then came the tragedy of World War I. And then came World War II. And after World War II, Europe was the stage in which the major Cold War performance was taking place. Everything was about divided Berlin. After the end of the Cold War, Europe was not anymore the major stage for economic and other reasons.

There was a move to Asia and to the Pacific. Both, particularly the United States, were less of a European power than they were before. Now we’re seeing the same for Russia.

But Europe found a role for itself. And Europe positioned itself as a laboratory of the world to come. European integration.

So, you have really kind of a continent-sized economy. You have these post-sovereign, post-modern states. And to be honest, it was a brave experiment. It has achieved a lot. And Europe has been imitated in many places in the world. So, in all this time, Europe was looking around itself.

The cliché was that we are surrounded by the future members. And the idea was how we’re going to transform them. And in the last decade, particularly after the annexation of Crimea, the problem was not how you’re going to transform them, but how they’re not going to transform you.

And Europe slightly was moving from a missionary to a monastery. So probably we’re not going to transform others, but we want to keep our way of life. And then came Russia’s full-fledged war in Ukraine. And then came Trump. And the European project has to change dramatically.

You say that Europe was haunted by not so much its failures, but its successes.

For example, the biggest European success is that it made war unimaginable as it came. Secondly, one of the major European projects was that it created a very competitive economic system within the European Union. But then as a result of it, we cannot end up with any big global companies which are going to compete globally, because all our competition rules were very much focused on not allowing anybody to dominate European markets.

And this was very much in the interest of small and medium-sized countries. It makes sense, but now it works against us. So from this point of view, the European Union is going to be forced to reinvent itself tomorrow.

How would that reinvention be?

All the clichés from yesterday, both of the pro-Europeans and anti-Europeans, do not make sense. If the European Union is going to survive and to make it, paradoxically it’s going to be a strange mixture of integration and disintegration at the same time. Europe will get more integrated in certain areas and less integrated in others.

For example, enlargement of the European Union is not going to be driven so much by how similar the countries are becoming, but by how geopolitically we are trying to consolidate this place. And this is in a strange way a different Union.

We still use the old language. We still use the old institutions. To try to see the situation as a new one without scaring the people, in my view, is the major challenge.

And also as a result of this process, countries are in different places because of their economies, because of their history, because of their demographies. So we should try to find a new way to get this unity, which should not be simply institutional unity, but it’s going to be something more. At the same time, this crisis produced several positive things.

After every crisis, Europeans started to know much more about other European countries. For example, the economic euro crisis came, and everybody knew the Greek economy or the youth unemployment in Spain. So suddenly, Europeans were living much, much more together.

With the war in Ukraine, suddenly it became clear that, yes, there are different positions, different interests and so on, but Europe cannot simply be the vegetarian at the dinner of the cannibals. So you should try to do something about this. And economically, I do believe that nation-states, for very good reasons, are trying to keep everything for themselves.

But if they are not going to become a capital market, they are never going to be a really highly developed, innovative technological complex. And also our relations to the United States have changed, our relations to Russia, our relations to Turkey, our idea that we’re going to attract Indians, Japanese and others, they make sense on one level, but we do not look as attractive and as powerful as before. And for many outside, the moment we look weaker, it’s going to make them even more aggressive.

Part of the problem of the European-Russian relations is that Russians used to think in terms of their own history. They basically think of the European Union very much as the late Soviet Union, and if this is the case, they’re going to do things which we don’t want to be done to us. So from this point, I do believe that for the European Union it’s very important to recognize the situation.

Europe has a lot of problems, but it’s not that others do not have them. You don’t want to be in the United States these days, a country in which fear of civil war is very much in the air. And China is very powerful on one level, but of course they have the economic and demographic problems which are also tough.

We don’t know how their model that worked quite successfully will allow them to cope. Russia probably is taking military advantage in Ukraine, but in the long term, this was a war which was totally disastrous, a special operation that should have been finished long ago. Now in January, the war in Ukraine is going to be longer than World War II for the Russians.

And keeping in mind the demographic goals for Russia and Ukraine, this was devastating. How many people have been killed? How many people were not born out of it in a situation where demography is so important?

So from this point of view, Europe is not in a principally different position than anybody else. And even countries who believe that they are on the rise, for example China, or Brazil and others, they also have their problems. So in the 1970s, there was a famous phrase which was coined by Pierre Aznar, a very interesting French political and strategic thinker who talked, because in the 1970s, you can imagine on the Soviet side, Czechoslovakia, on the Western side, Vietnam, he said, this is a competitive decadence.

Who is doing worse? And I believe for Europe it is very important to try to formulate some short-term objectives and to come with small victories which are going to allow people. And they are going to be difficult political bargains, because obviously there should be some institutional changes.

I cannot imagine that any country is going to join the European Union now if basically they are going to get a veto. These countries are going to be given other incentives to join, which means that the moment this is happening, the cohesion is going to be challenged. But this is going to happen.

And the problem is to find a much more creative way to do these changes as a result of strengthening it. I always believed that the strength of any major political project is survival. Anytime you survive a crisis, you are more legitimate in the eyes of your citizens.

This is what the nation states have been doing all their history. So the European Union was not prepared for tragic choices. And we are entering a moment of tragic choices. The return of tragedy, that’s what we see.

Not the death of tragedy, but its rebirth.

Yes, absolutely.

I remember that argument about the duration from your book After Europe.

Yeah, but this for me is a very important argument. You know, Rilke has this famous poem, who speaks of victory, to endure is all. You should be able to survive, you should have a capacity to change. In my book, capacity for self-correction is the most important characteristic in any political system. And if you succeed to do this, this is what really matters.

And paradoxically, in a moment like this, every government, every political leadership is facing the choice between rigidity and flexibility. And on this I have a very strong view, and this is flexibility. Don’t be afraid, there are certain rules that are going to be broken, there are certain new rules to be created.

And one of the things is that of course some old problems are also going to return to Europe, and Europe is going to deal with them. For example, for Europe there is no chance to get any type of defense autonomy if Germany is not going to basically create a much stronger army. On the other side, this coincides with the rise of AfD and the far right in Germany, and this scares many.

By the way, it scares many also on the far right in places like France and others. So Europe should try to also deal with this.

We’ve also seen the rise of extreme parties. Are they transitory phenomena or are they going to stay?

They are going to stay, they are going to form coalitions, so the question is if they are going to be integrated in the democratic system or not, or how they are going to influence the system. So from this point of view, many of the things that made sense before have changed.

For example there was a debate about whether some parties should be banned. You can ban a party if it has 5% electoral support. If one party has 20%, better not do it. Secondly, can you prevent certain coalitions? No. So then you should try to look for new narratives, new ways, but also objectives.

And this is happening in a moment in which many people are mistrustful and many people are frustrated. I know that everybody wants to be critical of politicians these days, but it’s much easier to be a political commentator these days than somebody who is taking decisions.

So recognizing the real issues that political leadership is facing, in my view, should be part of this realism that Europe needs at this moment.

Sometimes people say, Let the populists govern because they do a bad job and then they are out of power. And you say, no, the most difficult part is to get power the first time. Coming back is easier.

Well, they were coming back. At least in Eastern Europe. Mr. Kaczynski was out of power and then came back. And this was the case of Slovakia, this was the case of the Czech Republic. It’s different from country to country. But first of all, the economic policies of most of the populist parties are not so different from those of the mainstream parties.

And one of the major effects of populism is that it is like COVID, it affects everybody. And nobody was vaccinated. Even for countries like Germany and others, where people believe that the immune system is very strong, obviously it’s not the case.

So we should try to recognize that what we are seeing is not simply the crisis of democracy, but the transformation of democratic regimes. And there are certain things that are very important to preserve because otherwise the country is not going to be a democracy, but certain things are going to change. It’s not going to be the same.

You also say we went from a situation where stakes were very low to one where they are very high.

In the 1990s, regardless of who was in government, you were getting the same political policy. And this makes people very cynical. Now we are in a situation in which the stakes are very high, you’re losing elections and you fear that you can lose your freedom, you can lose your property. So from this point, you have to know how to rebalance, how to diminish this type of high-stakes game and at the same time to make politics meaningful for the people so they have a reason to vote.

You are fond of Napoleon’s quip that, to understand a man, you have to think of how the world was in his 20.

Institutions are important, but the most important are the fears of people, the hopes of people. They’re not theoretical. And as a result of it, political parties are going to be successful when they manage to mobilize these hopes and these fears and try to make a much more stable coalition around them.

But the level of volatility is very high –volatility on the market and volatility in national politics is very high. In Europe, in one country, populists are going to win, in another they’re going to lose. So how to try to have basically a political project in which very different parties are going to play?

And here’s one paradox. Ten years ago, there were a number of major European parties on the far right who saw the future of their countries outside of the EU. So now we have the same parties, probably as nasty as they were, but none of them was driven to leave the EU.

Every story is about transforming the EU. So we’re in a moment in which a kind of a new social contract on the level of the EU also is going to be signed, and it’s going to force compromises on all sides. And of course, President Trump and President Putin are going to be two of the shadows under which these contracts are going to be signed.