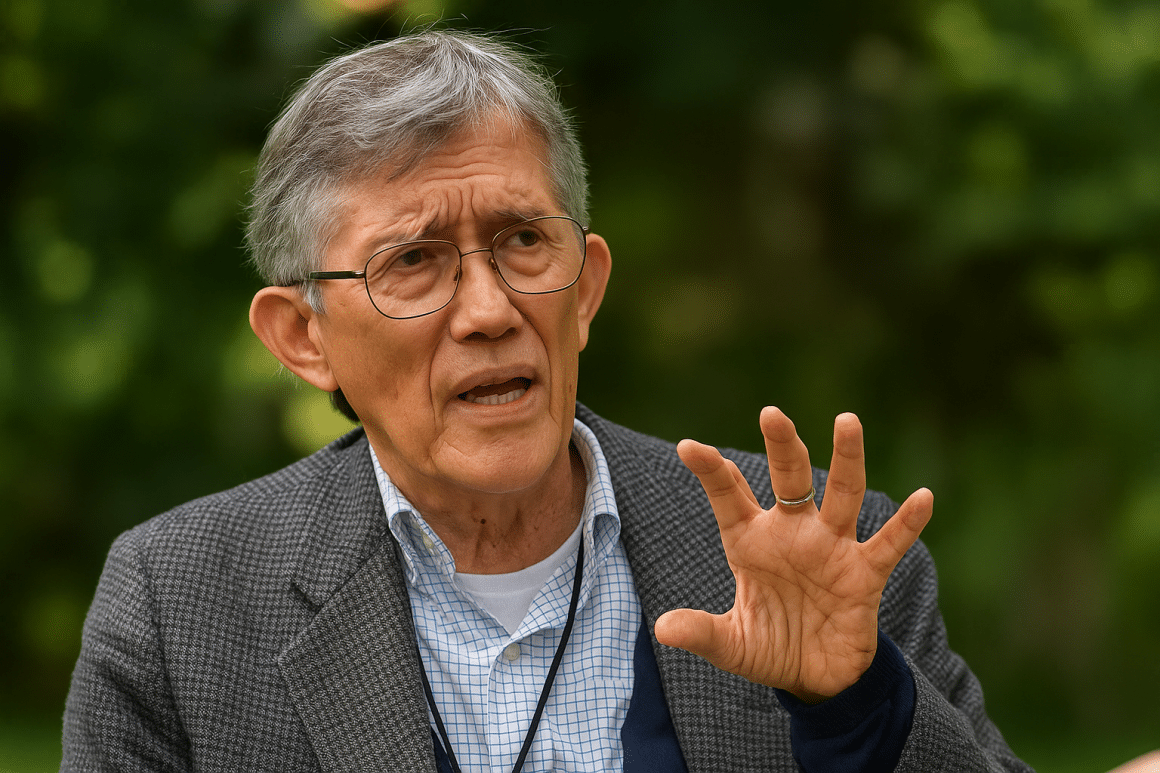

The career of evolutionary biologist Antonio Lazcano (Tijuana, 1950) is inextricably linked to the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), where he graduated as a researcher, studied for his PhD, and founded the Origin of Life Laboratory, which he has directed for decades in an attempt to use genetics to unravel one of the main mysteries that still haunts human beings: where we came from. Through more than 150 articles, books, and lectures, Lazcano has brought to the scientific arena a debate that began in philosophy and where politics has played a transcendental role, especially during the turbulent 20th century. He has received numerous national and international distinctions for his work, standing out as one of the great scientists of Latin America.

The discussion about the origin of life has always oscillated between the philosophical and the scientific. Is your career an attempt to tip the balance definitively toward the field of science?

Absolutely, but if I try to look at it from a scientific point of view, it is because I have a very poor philosophical background, as is unfortunately the case with most scientists. But I do not disdain the philosophical aspect.

In fact, the idea of how life arises has to do with the very ancient notion of a uniform universe. It is beautifully developed, for example, in De rerum natura by Titus Lucretius Carus, from the 1st century BC, and later in the Eastern philosophical tradition and in medieval theologians. And in the 19th century, this became a very strong obsession.

This is where the Russian biochemist Aleksandr Oparin comes in, someone who had a great influence on you, both as a scientist and as a thinker.

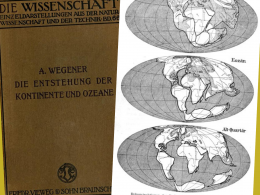

From the outset, his hypothesis convinced me. Oparin’s century-old theory holds that life did not arise suddenly, but is a process of chemical evolution, a non-biological synthesis of compounds. When we question the origin of life on Earth, what we are actually doing is appealing to a dialectical materialist view which, thanks to Oparin, also recognizes the process of evolution. Then serious problems arose. For example, the idea that there is a chemical asymmetry had to have a physical or chemical basis because Oparin, as an orthodox Marxist, did not accept giving chance a scientific role, whereas today we have other, slightly more flexible definitions of chance.

So as not to overwhelm the reader, could you summarize your current position on this issue?

I reject the idea of an initial living molecule. I believe we have to recognize a stage in the evolution of these organic compounds where they formed systems that began to interact with each other. I am very interested in the nature of these interactions; I want to know the details. And I was one of those who proposed, independently, that ribonucleic acid (RNA), the ugly duckling of molecular biology, played a central role in the hereditary processes of the earliest forms of life. But this narrative I am telling you is misleading, because I am not talking about the gaps we have in this story. John Bernal, a crystallographer and also an orthodox Marxist, said that Oparin’s great merit was to have told a narrative that allows us to identify the gaps so that we can concentrate on how to study them. What we do in Mexico is to see how far back we can take molecular phylogenies, make evolutionary trees using the available genetic material, and how we can try to reduce those gaps.

And what limits are you encountering? How far back can you turn the clock?

We don’t really know when life first appeared. The general consensus is that it happened around 4 billion years ago, when the planet was very young.

That’s part of the appeal of the origin of life: you have to combine knowledge of astronomy, geochemistry, planetary science, chemistry, biology, biochemistry, molecular biology, and so on. You run the not insignificant risk of becoming a jack of all trades and master of none. So you have to focus on a particular phenomenon.

One of the clear limits we have is that we cannot go back before there was a ribosome, a complex molecular structure where proteins are synthesized. We don’t know what happened before that. One can theorize from the properties of RNA how the first proteins were formed, but what guarantee do I have that the molecule I am studying as ancient had modes of expression and modes of functioning in this remote past that are equivalent to what we see in living beings today?

We have identified very ancient genes and proteins. Molecular biology is a reductionist discipline, yet living beings are not a random collection of molecules. I may have a very comprehensive dictionary of Spanish, but the dictionary does not allow me to predict a poem.

Just as in physics there are machines capable of trying to recreate the early universe, would this be impossible in biology due to the infinite combinations of chance?

Well, chance or not, because biology is not a story of coincidences. Chance is an essential component of the evolutionary view, but at the same time, natural selection acts on that randomness. You can get very precise results from random systems. For example, we have no more accurate clocks than those resulting from radioactive decay. But if you have half a kilo of uranium, you don’t know which atom is going to decay. It’s a random process, and yet the sum gives you an absolutely deterministic result. In biology, that can happen.

A machine that attempts to reconstruct the biological past would be every researcher’s dream, but unlike physicists or cosmologists, here you always have to consider the interaction with the environment, with a planet that has evolved over time.

Yes, rather than “random,” I should have said: the environmental context that we do not know.

There is a wonderful book that was published in 1970, Chance and Necessity, by Jacques Monod, which is a reflection of precisely that mechanistic materialism that prevailed in molecular biology in the 1970s and gave rise to a philosophical debate with political overtones, because Monod had been a member of the French Communist Party, fought in the resistance, and broke radically with the Soviets over the Lysenko affair.

[Trofim Lysenko was an agricultural engineer who for decades defended pseudoscientific theories aligned with Marxist principles: genetics was the enemy of the working class and DNA was superstition. Despite the erroneous nature of his theories, he became a reference point for Stalinist agricultural science and led to the purge of critical scientists].

Oparin, at the least lucid and most shameful moment of his career, was close to Lysenko and Stalin. And there, what we saw was a mechanistic materialism like Monod’s and a more evolutionary materialism, that of Oparin. I am fascinated by the history of science because it allows us to understand how our concepts work and to explain how to approach questions such as the nature of life without the dogmatism into which we inevitably fall.

I am surprised that the USSR is coming up so much in this talk. It reminds me of the war against bacteria, with the Russians researching bacteriophages and the Americans penicillin.

There was a fascinating microbiologist, Félix d’Herelle, who had a wonderful life of adventure. First in the Soviet Union, until his best friend got into trouble with the wife of a politician close to Stalin and they had to flee. He traveled all over the world with little boxes where he kept a cocktail of microorganisms that caught his attention. He ended up in Guatemala, where he invented a banana whiskey that must be awful. While there, he came to Mexico to work on the haciendas of one of Porfirio Díaz’s ministers to see what diseases could attack the plants.

One day, a group of farmers warned him of a locust plague. The insects flew into his face, hurting him. When he bent down, he saw locusts kicking on the ground. He took them to his laboratory, performed a premature autopsy, and placed the intestinal contents in Petri dishes. Days later, he realized that some bacterial colonies had circles where no bacteria grew.

After also fighting with the Mexicans, he ended up at the Pasteur Institute in Paris. World War I broke out, and d’Herelle, realizing that many soldiers were dying of dysentery, remembered what he had observed in Yucatán years earlier. He then repeated the experiment, purified the viruses that were attacking the bacterial colonies, and began giving vials of bacteriophage viruses to soldiers to save their lives.

The wall and its subsequent fall changed the history of so many scientific disciplines.

With the Iron Curtain, the Cold War, and Stalinism in the USSR, scientific relations between the two sides of the world were severed. The weight of Marxist ideology was tremendous on the development of Soviet science.

Loren Graham, probably the greatest historian and analyst of Russian science, demonstrated in an analysis that the methodological problems that developed in both the Soviet Union and the West were basically the same. There were ridiculous disciplines on both sides, let’s not forget phrenology. But then there was the language barrier, nothing was translated, and finally, the collapse of the Soviet scientific apparatus.

I have been very struck by all these interactions, by Oparin of course, but also because I am convinced that, even if we try to make science as objective as possible, the socio-political environment in which we grow up biases our perception of reality. And even more so when you are working on a problem as critical as the nature of life.

There is a lot of talk about the competition between the US and the USSR as the driving force behind the space race. Do you think that collaboration between the two would have taken us further?

I read a very moving essay by a researcher at the Weizmann Institute in Israel, who recounts the damage caused by the Iranian bombings at the institute. But in his plea, he repeats several times: “We have very close collaborations with Iranian colleagues. We are working on similar problems.” In other words, he acknowledged that, even though you cannot ignore your political or ideological identity, there are problems that unite you. It is moving to see a scientist recognize the brotherhood, so to speak, in intellectual and scientific interests with the Iranians, in the context of a conflict that is one of the most terrifying we are witnessing.

I understand that each scientific discipline has, so to speak, its own sociology.

Yes. NASA always considered the search for extraterrestrial life. In the Soviet case, it comes from a somewhat mystical 19th-century tradition of thinking that life was a very common phenomenon in the universe. For example, Tsiolkovsky, the father of Soviet astronautics.

In the 1960s, NASA began to seriously consider the possibility of searching for life on Mars. They asked an English scientist, Jim Lovelock, a close friend of Carl Sagan, to look at the data on the Martian atmosphere, and he said: “It’s in chemical equilibrium, I can explain its composition by purely physical arguments, and I see nothing that points to the existence of biological activity.”The efforts of colleagues, especially planetary astronomers, to search for extraterrestrial life are very legitimate, but I also believe that the evidence is very poor. I like to say that extraterrestrial life is like democracy: everyone talks about it, but no one has seen it.