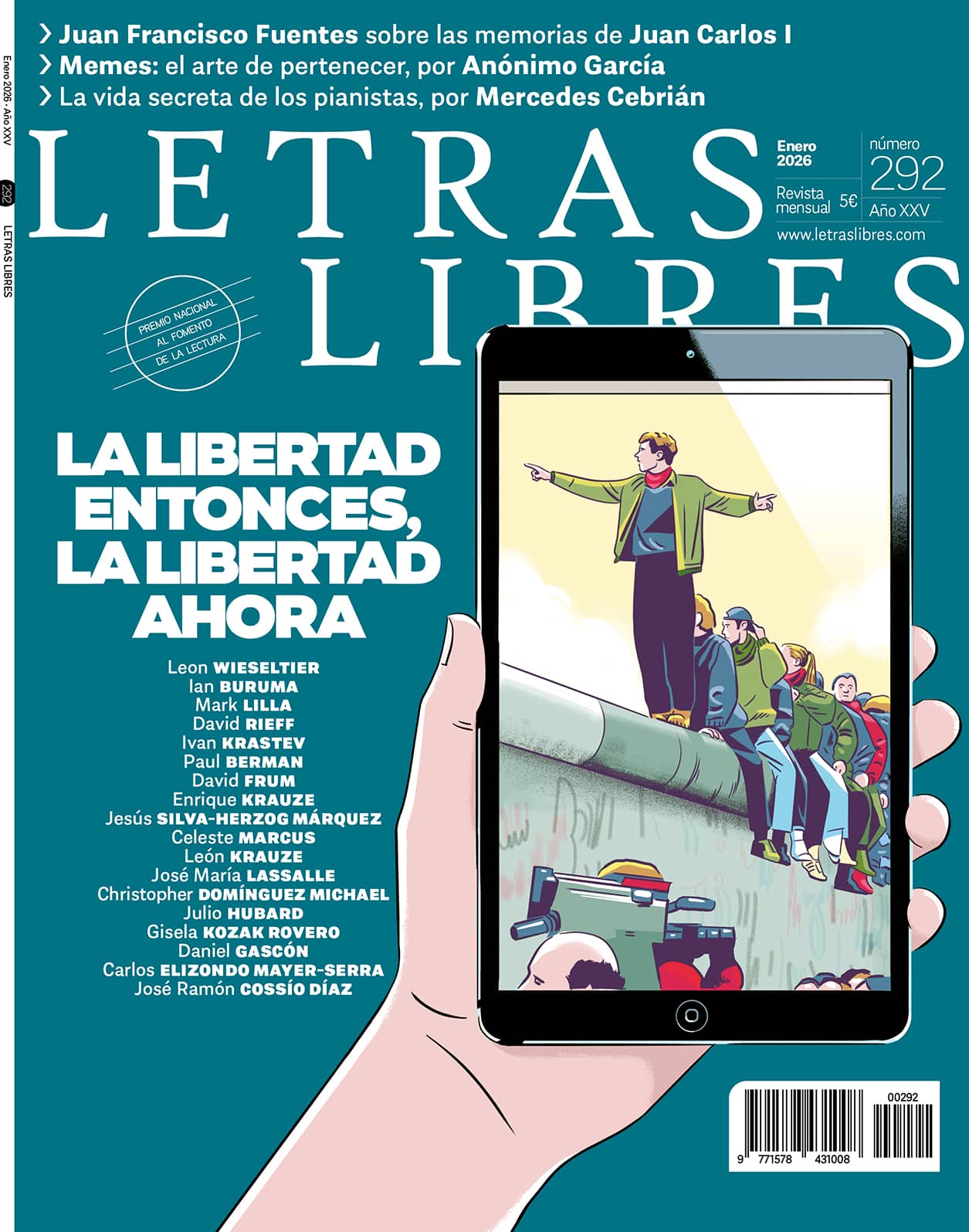

It is often said that the traditional division of parliaments into “left” and “right,” beyond its historical origins in the French Revolution, is due to the need for modern societies to make maximum freedom and maximum equality compatible.

In a free society, factual inequalities can never be completely eradicated, since the social game, precisely because it is free, will necessarily generate differences in outcomes. Similarly, in a society of citizens with equal rights, not all limitations on freedom can be eliminated, although they must always obey the need to ensure that everyone is equally free. For this reason, policies of equal opportunity and policies of expanding freedoms, although circumstantial in their intensity and application, are structurally necessary. And although it is also customary to identify “left-wing” parties with equality policies and “right-wing” parties with freedom policies, history has shown that this rule cannot be generalized, as we have often seen the right defend equality before the law and the left defend civil liberties.

As John Rawls demonstrated, if it is necessary to add the principle of fraternity to these two principles (freedom and equality), it is because, where men are freely equal and equally free to choose their life project, their beliefs, or their tastes, the only thing that sustains coexistence and social ties is the law, and no one would accept a law that would abandon them if fortune turned against them because they had become old, lame, poor, or sick.

When Ortega y Gasset wrote that “being on the left is, like being on the right, one of the infinite ways in which man can choose to be an idiot,” the “idiocy” he was referring to is that suffered by those who are not content to vote freely for the left or the right according to their own criteria and situation, but instead align themselves with one of the two sides for life, as a believer in a religion of salvation would do, because they consider it intrinsically superior to the other, thereby denying the equality of citizens on the other side (whom they consider intellectually or morally inferior) and also questioning their freedom. But this “idiocy” would not have become so important without the existence of 20th-century totalitarianism, which represents a frontal rejection of the Enlightenment heritage I have just referred to and promotes restrictions on freedom or equality that, according to that heritage, would always be illegitimate because they imply the destruction of parliamentary democracy and the rule of law.

Although we Europeans consider totalitarianism to be a thing of the past (which is saying a lot, given that authoritarian regimes are in the majority worldwide), it has also left a considerable political legacy among us. If this legacy is more visible on the left, it is for two reasons: one is historical and has to do with the fact that Stalin’s position against fascism in World War II created the optical illusion that communism was opposed to totalitarianism, when in fact it is its most enduring version. The other is intellectual, and refers to the prestige of Marxism as a supposed “scientific theory” of society and history (a prestige that, of course, is not shared by social scientists who, as such, have freed themselves from ideological prejudices). Certainly, European social democracy largely abandoned both the communist project and Marxist doctrine after the aforementioned war, but the economic crisis of 2008 brought a series of electoral setbacks which, in the case of Spain as in others, caused a shift towards more extreme positions on the political spectrum, although it is not easy to discern how much of this relocation is simply opportunism.

Of course, except among prominent philosophers, today the left does not claim the term “communism” and does not even use the word ‘capitalism’ to designate its political enemy. Instead, the expression “neo-liberalism” was coined, which began to function as a new name for that enemy after the Argentine debt crisis of 2001. The core of this neo-leftism, which generously mixes doses of classic caudillismo with positions of the so-called American “new left” and French poststructuralism, abusively summarized, is the idea that “neoliberalism” not only exploits the people, but also creates specifically neoliberal forms of subjectivity, that is, subjects who actually desire their own exploitation. This would explain why the two politicians that this new left considers emblematic of neoliberalism, Reagan and Thatcher, far from imposing themselves as dictators, were democratically elected and re-elected (twice the former, three times the latter) in free elections and in countries where the separation of powers and freedom of the press reign. But for this new left, it is also proof that democracy fails, that the working classes vote against their own interests (although, in Ortega’s terms, it could rather be a symptom of their having ceased to be “idiots”).

And it is this distrust of liberal democracy that, at least in Spain, has led to a shift to the left towards populism, that is, towards a valuation of “popular sovereignty” that discredits the institutions of the rule of law as enemies of “social justice” or, in Carl Schmitt’s terms, places legitimacy above legality. Thus, political alternation, which in a healthy democracy is the very expression of the irreducible pluralism of free societies, is often presented as a catastrophe to be avoided at all costs.

This is all the more serious when the government, due to the fragmentation of parliament, does not represent a large majority, but is constituted as a sum of minorities. All of this has, on the one hand, produced the astonishing and dangerous convergence of left-wing parties with Catalan and Basque secessionists, who also consider that the will of their “peoples” is oppressed by constitutional legality and, on the other hand, has caused a conflict between the executive and judicial branches that is difficult to resolve and has translated the parliamentary confrontation between the left and the right into a division that now runs through civil society, threatens the principles of coexistence, and undermines the credibility of the media and the entire public opinion system.

The Spanish right is affected by this same process of populist degradation, in terms that reproduce, on a scale certainly less tragic than in other times, the same confusion that in the past affected the debate on Totalitarianism: just as it was aberrant to argue that there is a kind of “good” Totalitarianism (that of the left) as opposed to a bad one (that of the right), because the pluralism that presupposes the distinction between left and right is what totalitarianism eliminates with its single-party regimes, so too is it ridiculous today to contrast “good” populism with “bad” populism, because the evidence that both are one and the same is overwhelming. Although it is true that, in Spain, the main center-right party has not yet succumbed to this drift, it is also true that this leads to its electoral weakness, because populist polarization always favors the extremes.

However, democracy does not allow for saviors, and when it is in danger, only democracy itself can come to its rescue. Democracy is not just, as Churchill said, about not fearing that the police are coming to arrest us when the elevator bell rings at six in the morning. It also consists of not going to vote out of fear that, if those who do not think like us win, we will be condemned to social death, but rather of doing so with the freedom that comes from the certainty that, even if the others win, we will continue to be part of the game, just as the others will continue to be when our side wins. For elections to be truly free, those who vote in them must not do so as if they had to choose between Jesus and the Antichrist or between Spain and Anti-Spain. In other words, they must not feel that their vote or that of their opponents could destroy their country, and they must know that the losers will continue to be part of the same nation, because it is ultimately for that nation that they are voting. The defense of freedom and equality is only possible in an environment of fraternity. And it is we, the voters, and not the politicians who claim to know better than us what is good for us, who have the responsibility to free ourselves from the fear induced by propaganda and renounce our “idiocy” (in the Ortega sense).

In other words, in order to be able to vote without fear or anger on the left or the right, we must first have chosen, in our hearts, between liberal democracy and that other thing that is supposedly better, but which we know perfectly well from experience how it ends. And in that prior choice, we are not choosing between different parties, but choosing the possibility of orienting ourselves autonomously. And if, as Kant reminded us, in order to orient ourselves in space we need to feel the difference between our left and right hands, in order to orient ourselves politically there must be more than one party and, therefore, there must be left and right, equality and freedom. It is enough for us to be aware that we do not want a story with a happy ending, but one in which we, all of us who vote, write the ending.